Here we will discuss Paul Olaf Bidding and his published works relating to folklore. It discusses his role in documenting the oral folk literature of the Santal tribal community of Santal Parganas.

It goes on to discuss the three-volume ‘Santal Folk Tales’ translated by Paul Olaf Bodding and studies various folkloric elements present in the folktales.

The tribal groups of Jharkhand

The tribal groups of Jharkhand are societies that had an oral tradition till European ethnographers; started documenting and writing down their traditions like folk epic, myths, legends, folk tales, proverbs; and riddles, folk songs, poems, and performances associated with them.

These oral narratives constituted a body of knowledge and the collective memory of the people. Much of the early work of collecting and documenting the oral narratives of the Jharkhand tribes was done by anthropologists; folklorists, and missionaries working in the region.

These collected narratives were often written down in European languages; and sometimes in the tribal languages themselves using the popular existing scripts like Roman, Bengali, and Devnagri.

Some scholars took it upon themselves to translate their folk tales, poems, songs; etc into European languages like Norwegian and English. A number of such translations were published and archived for research.

For a long time, these writings were considered to be of interest only for the social scientist and anthropological; and ethnographical research but a growing interest in oral narratives across the world has changed this attitude.

The study of oral narratives of the indigenous communities in Africa, America; and Australia has been introduced in many Universities; and schools across the world as academic courses in Oral Literature, Orature, and Folklore Studies.

Tribal oral narratives in India have now gained recognition as the ‘voice of the subaltern’ within the broad sphere of Literature from the Margins.

The Santal society

Santal or Santhal society was a pre-literate society till the mid-nineteenth century. The first attempts to write in Santali were made by an American Baptist missionary of Jellasore Rev. Jeremiah Phillips (1812-1879); when he published ‘An Introduction to the Santal Language’ in 2 1852 using Bengali alphabet to write Santali.

In 1873 Rev. Lars Olsen Skrefsrurd (1840-1910), a Norwegian Lutheran missionary of Benagaria Mission in Dumka; published ‘A Grammar of the Santal Language’ used the Roman alphabet to write Santali.

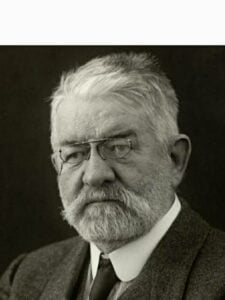

Paul Olaf Bodding (1865 – 1938)

Rev. Paul Olaf Bodding was a Norwegian missionary who came to India in 1890 and immediately set about learning Santali. His work in India was mainly to take over and continue the literary program initiated by Rev. Lars Olsen Skrefsrud of the Santal Mission in Santal Parganas.

Santali is a difficult language and he spent much time with the people to learn it thoroughly and idiomatically. He had undertaken the study of languages and ethnography in school to prepare for this task.

The “Bodding kora” (Bodding boy) as the Santals fondly called him was exceptionally gifted and very capable of discovering the specialties of the Santali language.

In the Introduction to ‘The Folklore of the Kolhan’, Pallabh Sengupta, Arpita Basu, and Sarmistha De Basu state thus ‘Rev. Bodding’s scholarship and erudition were well-known to all.

He had very closely interacted with the Santals for a pretty long time and consequently became an authority on their life, lore, and language. He readily introduced Bompas to the social and cultural orbit of the Santali people.

As a consequence of this association, Bompas translated 185 Santali folktales into English from the collection of Rev. Paul Olaf Bodding. These translations formed the main corpus of his well-known book ‘Folklore of the Santal Parganas’.

W.G. Archer

W.G. Archer worked in the Indian Civil Services and 16 years in Bihar has authored a couple of books on the Santals.

In the preface of his ‘Hill of Flutes – Love, Life, and Poetry in Tribal India: A Portrait of the Santals’ he pays high tribute to ‘… the great Bodding …’ praising him highly.

He further adds ‘… his huge Santal-English dictionary staggered me by its encyclopedic learning and gave me indispensable help.’

LSS O’Malley of Indian Civil Service and writer of ‘Bengal District Gazetteers

Santal Parganas’ acknowledges the contribution of Paul Olaf Bodding to his book. He writes that the entire chapterIV (total 62 pages) of the book was written with the help of Rev. Paul Olaf Bodding.

He states that ‘This chapter has compiled with the help of Rev. Paul Olaf Bodding of Mohulpahari, whose kindness in revising the draft and contributing large additions I cannot too largely acknowledge’.

Paul Olaf Bodding and Santal Dictionary

For his literary work, he usually had a group of co-workers (from two to six) whom he referred to as his ‘living dictionary’.

Sido of Ambajora village was the leader of the group assisting Paul Olaf Bodding with his work on the massive ‘Santal Dictionary’, which was his main aim at that time.

These workers who were literate were of great help in collecting and writing the stories and folklore. One of them – Sagram Murmu from Mohulpahari was considered to be an expert writer and it is he who has documented most of the stories collected by Paul Olaf Bodding.

Major literary contributions of Paul Olaf Bodding

Santali

- Kuk’li Puthi (Book of Riddles), 1 st edition, Benagaria Mission Press, 1899

- Kuk’li Puthi (Book of Riddles), 2nd edition, 1935

- Hor Kahniko (Santal Folktales) , Benagaria Mission Press, 1924

Santali with English Translation

4. A Chapter of Santal Folklore, Kristiana, 1924

5. Santal Folktales, I, II, III, Oslo, 1925 – 29

English

6. Materials for Santali Grammar I, Mostly Phonetical, Benagaria Mission press, 1922

7. Materials for Santali Grammar II, Mostly Morphological, Benagaria Mission Press, 1929

8. A Santal Grammar for Beginners, Benagaria Mission press, 1929

9. Studies in Santal Medicine and Connected Folklore, part I, Calcutta -1925, part II – 1927, part III – 1940

10. A Santal Dictionary, I, II, III, IV, V, Oslo 1929 – 36

11. Traditions and Institutions of the Santals, Oslo, 1942 (Translation of Skrefsrud’s Mare Hapramko).

Articles in English`

- The Meaning of the words ‘Burus’ and ‘Bongas’ in Santali (Journal of Bihar and Orissa Research Society, Patna – 12 (I) March 1926)

- Further Notes on ‘Burus’ and ‘Bongas’ (Journal of Bihar and Orissa Research Society, Patna – 12 (2) June 1926)

- Witchcraft among the Santals (Oslo Ethnographical Museum, 1940)

- A Note on the ‘Wild People’ of the Santals (Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta, New Series, 27 1931)

- Santal Riddles (Oslo Ethnographical Museum, 1940)

- Notes on Santals (Census of India)

- The Different Kinds of Salutations Used by the Santals (Journal of Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta, 67 (3) 1898)

- The Taboos and Customs connected therewith among the Santals (Journal of Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta, 67 (1) 1898)